WRITTEN BY VICKY REDWOOD of Capital Economics

- There is no doubting that governments have generally pulled out all the stops in announcing big fiscal stimulus programmes. But announcing them is one thing; quickly getting the money to where it is needed is quite another. There is a risk that logistical problems prevent fiscal policy from shoring up economies quickly enough to prevent the initial virus-related recession from turning into something more serious.

- Some say that fiscal policy is not effective because people are unable to spend any handouts while vast swathes of the economy are simply shut. We disagree for two reasons. First, giving money to low-income people who have lost their jobs will allow them still to buy food, pay their rent etc. So it will boost output in the sectors of the economy that are still open and providing essential goods and services. It won’t stop a dramatic drop in output while shutdowns are in place, but it will prevent that drop from being even bigger.

- Second, and more importantly, the fiscal stimulus programmes are not primarily about stopping a big contraction in GDP now. Instead, they are about ensuring that economies can bounce back quickly once virus-related restrictions ease. That is why the biggest measures so far relate to supporting firms (through loan guarantees and deferred tax payments) so that they do not go out of business in the meantime.

- Nonetheless, the effectiveness of fiscal policy could still be hampered by logistical problems, given that it takes time both to design schemes and then to implement them. Indeed, on this front, fiscal policy is at a distinct disadvantage to monetary policy. A cut in interest rates can be enacted immediately and will affect the whole economy. In contrast, it is rare (if not unprecedented) for fiscal stimulus to be implemented as quickly as it is now. Moreover, there is no single mechanism through which a stimulus can be undertaken. Whatever scheme is used, there will be people and firms who fall through the cracks.

- There are constraints on how quick and effective even the most straightforward of schemes can be. For example, one of the most obvious ways to provide a fiscal stimulus using existing infrastructure is via government benefits. But there are widespread reports that US states are having trouble processing so many Unemployment Insurance claims with their dilapidated IT systems. Direct, universal handouts should also be one of the easiest things to do too – just give everyone some money, regardless of who they are. Yet in Hong Kong – the first to announce a direct payment to all residents back in February – the money is not yet on its way. And although US citizens are due to start receiving their $1,200 handout announced on 25th March in mid-April, there are concerns that it will take until Q3 to get everyone processed.

- And when it comes to providing finance to firms, things are even trickier. Because different types of firms use different types of finance, governments have had to start up a myriad of schemes, from purchasing corporate bonds to guaranteeing bank loans for small companies. And even this doesn’t capture everyone; not all firms have an existing relationship with a bank. Meanwhile, vetting borrowers takes time.

- All these logistical difficulties are exacerbated by the fact that governments are often making up these schemes as they go along, meaning that there are inevitably teething problems which delay their impact. For example, the UK had to soften the conditions of its new Coronavirus Business Interruption Loan Scheme a couple of weeks after its launch in order to improve its uptake and there are still problems.

- There is also some trade-off between targeting measures at those that most need it and just getting the assistance out there as quickly as possible. For example, governments don’t really want to bail out firms that were about to go bust anyway, or to give wage subsidies to the richest individuals. But the more complicated the scheme, the longer it takes and the greater the economic damage in the meantime.

- The bottom line is that governments are generally doing their best – but even their best may not be good enough. Regardless of how impressive the headline numbers attached to the fiscal packages are, there is clearly a risk that the money is not coming quickly enough to prevent a rise in unemployment and defaults. Indeed, the unemployment figures released so far paint a fairly grim picture.

For its part, here’s a look at action the Fed has taken in just the past six weeks:

- March 3 — An emergency 0.5 percentage point interest rate cut.

- March 15 — Another 1 percentage point rate cut, taking the Fed’s benchmark for short-term lending down to near zero.

- March 15 — At the same time as the second rate cut, the Fed lowered the rate for banks to borrow at the discount window by 1.5 percentage points and cut the reserve requirement ratio for banks to zero.

- March 17 — In the first of a slew of measures aimed at keeping credit flowing through the financial system, the Fed said it would start buying commercial paper, or the short-term unsecured debt that businesses rely on for operational cash.

- March 18 — Another facility providing credit to keep money markets functioning properly.

- March 19 — A new operation focused on currency swaps aimed at other institutions in need of dollar-denominated assets.

- March 20 — An operation headed by the Boston Fed to buy municipal debt.

- March 23 — An expansion of the Fed’s originally announced asset purchases, which were supposed to max out at $700 billion but now are unlimited depending on the need to support markets and the economy. The purchases already have expanded the Fed’s holdings on its balance sheet by more than $2 trillion.

- March 23 — In addition to the next leg of quantitative easing, the Fed also announced a $300 billion credit program for businesses and consumers. The initiatives include two credit facilities for large employers, an expanded Term Asset-Banked Loan Facility for businesses and consumers through the Small Business Administration, and an expanded money market facility that includes municipal debt and certificates of deposits.

- April 6 — An announcement that the Fed will provide support to the Treasury’s Payment Protection Program aimed at incentivizing businesses not to lay off employees during the coronavirus-induced shutdown.

- April 8 — A modification for the asset restriction it has placed on scandal-plagued Wells Fargo to allow the third-biggest U.S. bank to participate in the business lending programs.

- April 9 — The coup de grace, a $2.3 trillion lending programthat will extend credit to banks that issue PPP loans, purchase up to $600 billion in loans issued through the Main Street program to medium-sized firms. The moves also involve secondary corporate credit facilities that will allow the Fed to buy corporate bonds from “fallen angels” that have slid into downgrades, and a $500 billion program to buy bonds from state and municipal governments.

In all, the programs could combine to provide more than $6 trillion of liquidity to the financial and business system.

China Data Response

WRITTEN BY JULIAN EVANS-PRITCHARD of Capital Economics

Worse still to come for exports

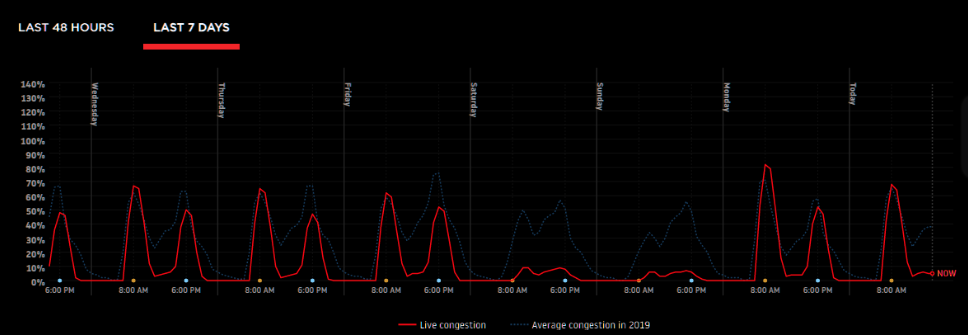

- Shipments picked up last month as factories re-opened and domestic demand began to recover. But with economic activity in the rest of the world now collapsing, the worst is still to come for China’s export sector.

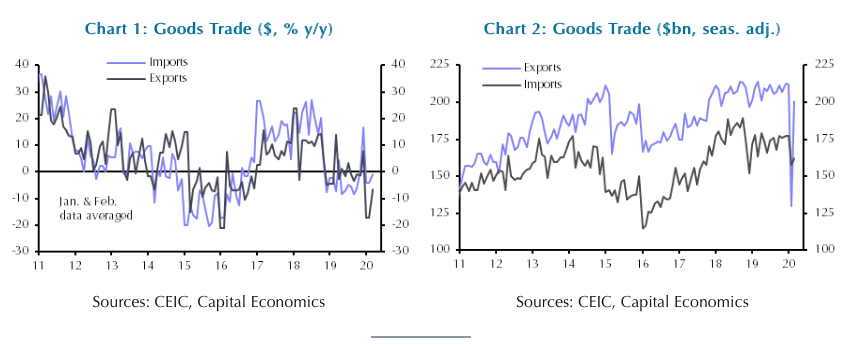

- The contraction in exports eased from -17.2% y/y in January and February to -6.6% last month in US Dollar terms (the Bloomberg median was -13.9%, our forecast was -20.0%). Imports also improved, from -4.0% y/y to -0.9% (Bloomberg median -9.5 %, CE -10.0%). (See Chart 1) Unusually, January and February’s trade data were published as a single combined figure this year.

- The improvement in trade was larger than the change in the headline figure suggests. We have disaggregated the data by assuming that trade was flat in seasonally adjusted terms in January, with all of the slowdown taking place in February. On this basis, exports increased 54.7% in seasonally adjusted m/m terms in March after falling 38.8% in February. Imports rebounded 2.8% after a 10.9% drop in February. But this improvement still leaves shipments at their weakest level in over a year. (See Chart 2)

- The recovery in exports is likely to be short-lived. Although supply-side disruptions to factory activity have now eased, foreign demand will slump this quarter as COVID-19 weighs on economic activity outside of China. Exporters are already bracing for this, with a drop last month in imports for processing and re-export suggesting that they are turning more downbeat on the prospects for global demand.

- Imports should hold up better given that domestic demand looks set to stage a further recovery in the coming months. But the quarter of China’s imports that feed into China’s export sector will continue to fall and hold back the recovery in imports.