Written by Neil Shearing, Group Chief Economist

28 April 2020

Last week I outlined how and when virus-induced shutdowns are likely to be eased. This week I discuss how the world may have changed when economies reopen.

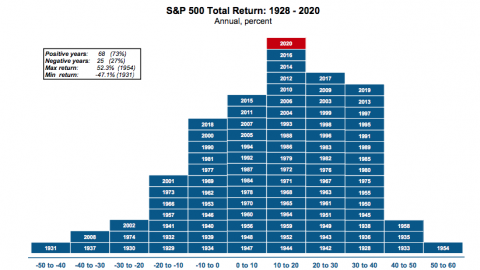

As I have noted before, the lockdowns have curtailed both supply and demand. Shuttering workplaces and restricting movement have reduced the ability of firms to supply goods and services. The same measures have also undercut demand (if consumers are housebound their ability to spend is greatly reduced). Added to this, a combination of dramatically reduced incomes and heightened uncertainty about the future has added to the drag on consumer spending and business investment. The combined result is likely to be the biggest fall in GDP this side of the Second World War.

As lockdowns are lifted, the supply potential of most economies should be restored relatively quickly; firms will re-open and people who were temporarily laid off or took unpaid leave will go back to work. Of course, this will not be possible if lots of previously solvent firms go to the wall during the shutdown. Indeed, some business failures are unavoidable. But as long as the substantial government support in the forms of loans and grants proves effective, we do not envisage a big permanent reduction in supply. And people are unlikely to lose their skills during only a short period of unemployment.

The picture surrounding demand is more complicated. Demand should rebound as lockdowns are lifted and some of the restrictions on spending imposed by the shutdowns ease. But several factors are likely to prevent a swift recovery to pre-virus levels. The balance sheets of some households and businesses will be impaired by the crisis, uncertainty will persist, and confidence will remain fragile. Behaviours may change too. Even if shops, cinemas, restaurants, and theatres re-open, individuals may be reluctant to gather in public spaces, thus depressing demand for these services.

All of this has implications for the speed and shape of the post-virus recovery.

It’s likely that we will see some strong growth rates over the second half of this year and the early part of next as shutdowns are lifted. But this would only reverse part of the huge fall in output experienced previously. Indeed, prolonged weakness in demand means that the level of GDP will remain below its pre-virus trend for several years. (For more, see our latest set of Outlooks, including the Global Economic Outlook, published last week.) One consequence is that inflation pressures will remain extremely subdued and policy support will have to remain in place for some time.

The virus will also have a profound effect on the world economy beyond the profile for GDP over the next year or so.

For a start, government debt burdens will be much larger as a result of the various fiscal measures that have been announced over the past month. As it happens, this need not necessarily be a major problem. After all, one of the lessons of the past decade is that in a world of low interest rates governments can sustain large debt burdens. For some countries, a combination of economic growth, low interest rates and the passage of time may be enough to erode debt burdens gradually. This is most likely to be true of countries that issue debt in their own currency, not least because they have more tools at their disposal to keep interest rates low (including forms of financial repression).

But countries that do not issue debt in their own currencies – including lower-income emerging markets and members of the euro-zone – face tougher choices. For some, default and restructuring may ultimately be the least unattractive option.

A second way in which the post-virus world may change relates to the role of the state. In 2008, governments backstopped the banks. In this crisis they have backstopped large tracts of the non-financial corporate sector too. In the process, governments have expanded the range of powers at their disposal. Of course, it may be that governments step back as the crisis recedes. But this is not a given. New powers are often easy to acquire but difficult to give back. Meanwhile, the public mood may be shifting – there are signs that the spirit of individualism that has shaped the discourse over the past thirty years is starting to give way to a new spirit of collectivism. In truth, it is too soon to say how this will play out. But the prospect of a larger state would raise lots of challenging questions for policymakers, not least how to fund it.

Finally, the fallout from the virus may intensify the pushback against globalisation and multilateralism that had been building before the outbreak began. The absence of a co-ordinated policy response to the virus by major economies is already striking. Unlike in 2008-09, when governments and central banks co-ordinated their responses in global fora like the G20, this time measures have been announced separately and co-ordinated on national rather than supra-national lines. Meanwhile, populist leaders are already using the crisis as a platform to fire up their base and consolidate their positions. President Trump has suspended immigration to the US for 60 days, Viktor Orban has effectively suspended Hungary’s parliament as he is ruling by decree and Brazil’s president, Jair Bolsonaro, has upped the ante in his dispute with congress by throwing his support behind anti-democracy protests.

Once again, it is too soon to say how these events will develop. But it is easy to see how they could prove to be the thin end of a very long wedge. After all, as the virus fades, the recriminations will begin, providing yet more fodder for nationalists. On top of this, the disruption caused by the virus may cause firms to question the benefit of maintaining global supply chains. As the incoming data continue to crater, the focus will understandably remain on the immediate economic damage that is being caused by virus-related shutdowns. But investors should keep in mind that the virus is likely to have consequences beyond the next year. The effects will continue to reverberate long after the lockdowns are lifted.

How many corporations will see merit in flexible scheduling, if not complete remote, “work-from-home” staffing? There are offices all over Atlanta that have very high rent. If the folks within that space can be just as productive at home, why would a company want to have that kind of expenditures (rent/lease, utilities, etc.)? I can’t see how they aren’t at least looking at it in that light. A friend of mine’s wife works for corporate Home Depot. She has been working from home this entire shut-down; as an example.

Moreover, the part in the article about “Behaviours may change too. Even if shops, cinemas, restaurants, and theatres re-open, individuals may be reluctant to gather in public spaces, thus depressing demand for these services.” is the nail being hit on the head. I couldn’t agree more with that sentiment.