Single-family house prices have been rising at record rates, raising the question of whether they have become disconnected with fundamentals. In October 2021, U.S. home price appreciation reached an annualized pace of 20% almost double the rate in 2012 when housing was rebounding off its lows of the global financial crisis (GFC).

Yet, in our view, this cycle is different. We believe the single-family housing market is on much stronger footing today versus the pre-GFC period. Every entity involved in housing, including homebuilders, lenders, government-sponsored entities (GSE), investors, and borrowers, was in some way scarred by the financial crisis and has tended to behave more conservatively ever since. As a result, U.S. housing should remain supported over the long term by two pillars: a secular shortage of housing units and resilient, delevered borrowers.

In our base case outlook, we expect home price appreciation to slow in line with long-term trends and inventories to gradually recover off record lows. Affordability is likely no longer the tailwind it was in the summer of 2020 when mortgage rates plunged, but remains in line with long-term trends. If rates continue to rise significantly, affordability will likely pressure housing, but we expect the fundamental stability of the market limits the risk of a major correction. Further, we think that the emergence of institutional owners in the single-family rental market may be another source of price support in certain areas.

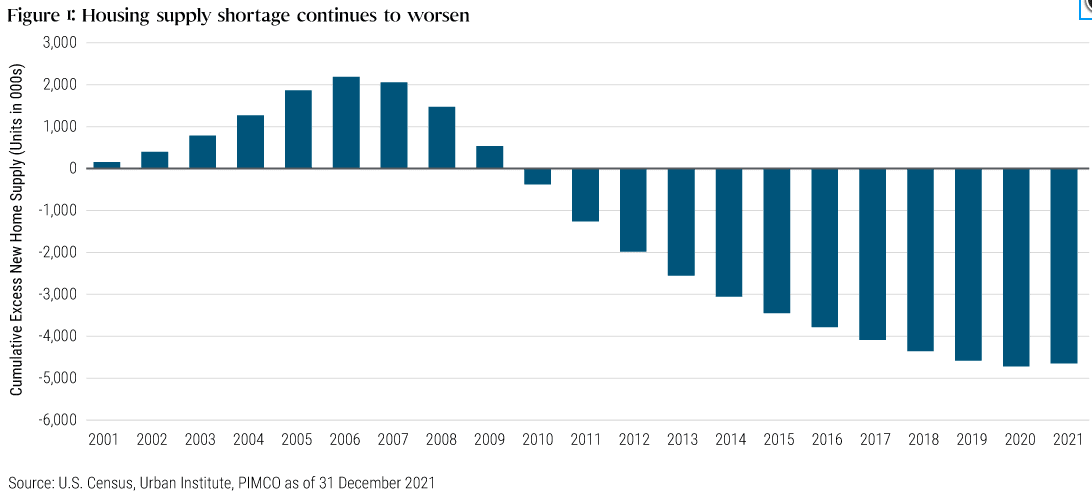

The secular shortage of houses remains unaddressed

Supply scarcity supports the current boom in U.S. home prices, a marked difference from the speculative bubble fueled by extremely loose underwriting that preceded the GFC (see Figure 1). Housing construction has lagged demand for nearly 10 years; the pre-GFC glut was absorbed long ago.

A confluence of circumstances underpin this scarcity. Lending standards have tightened, and banks have higher capital requirements for residential construction loans. Millennials are reaching prime home-buying age, and many older adults are staying in their homes longer. As a result, while homebuilders are close to building enough homes to satisfy the housing needs of current U.S. population growth, there remains a significant shortage of houses from the long period of underbuilding. Estimates of this secular shortage range from two to five million houses, while the current annual construction rate is just 1.6 million houses. We do not believe this imbalance will be resolved near term. Ramping up construction has proven exceedingly difficult: Building costs have ballooned amid supply chain bottlenecks and tight labor pools, and local zoning regulations often make developable land scarce. As one illustration, the cost of building materials increased by 7% (cumulatively) from 2015 to 2019, and then jumped 26% from 2019 to 2021

Lending conditions have remained very conservative

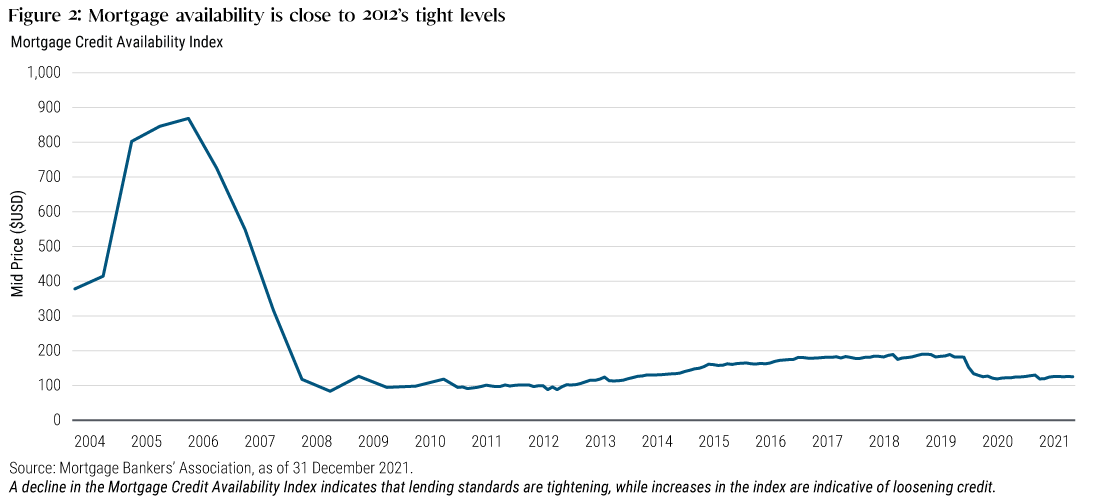

Unlike the house price boom that preceded the GFC, the current boom is driven by fundamentals: a lack of supply, as opposed to sharp increases in demand fueled by speculative lending practices. Demand for U.S. housing today is tempered by the Dodd-Frank Act’s underwriting standards, which eliminated certain speculative products, including negative-amortization loans, and by practices such as qualifying borrowers using low initial “teaser” rates on the hopes that borrowers’ incomes would rise to support increasing debt service. The ability to repay is now the law of the land. And the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is enforcing these laws, effectively eliminating speculative lending in the owner-occupant segment of the housing market (see Figure 2).

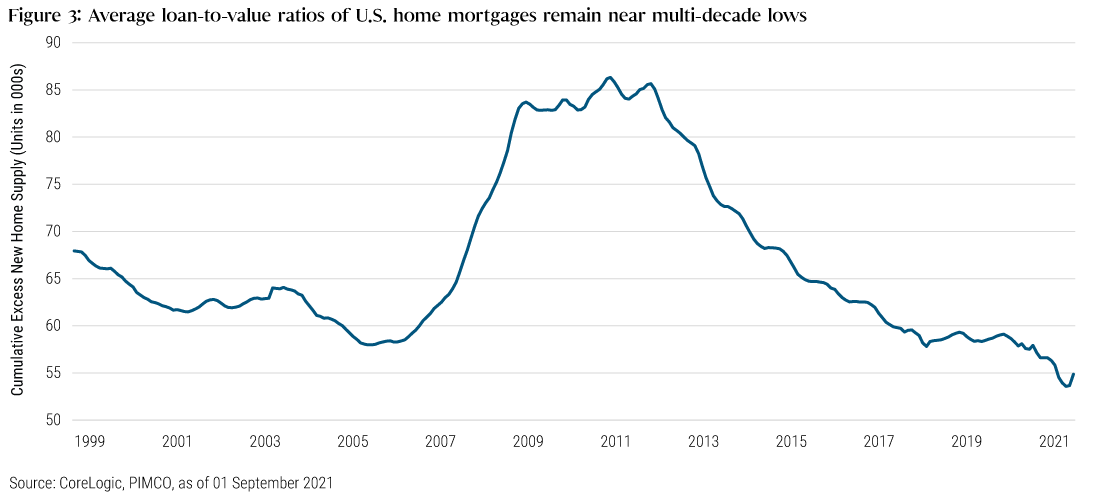

Borrowers have delevered and their balance sheets are strong

Today’s homeowners tend to have stronger balance sheets. Mortgage payments have declined along with interest rates, and after years of rising home prices, many homeowners have built sizeable equity, which they have not tapped through cash-out refinancing. As a result, the average mortgage in the U.S. has a loan-to-value ratio of close to 50% (see Figure 3). The total value of residential real estate in the U.S. is around $38 trillion, with approximately $12 trillion in outstanding mortgages. This leaves close to $26 trillion of equity in the market – a formidable cushion. Importantly, the large majority of the existing mortgage market consists of “vanilla” 30-year amortizing loans with fixed payments that delever over time. Therefore, even if rates were to increase sharply, we would not expect a flood of borrowers defaulting or selling because their mortgages suddenly became unaffordable.

Affordability remains supportive in many areas

The recent nearly 0.50% increase in mortgage rates exacerbates housing affordability, which prior to this recent increase was already at its lowest level since the GFC, due to the unprecedented run-up in house prices. The persistent affordability benefit from low rates is, thereby, now eroding on two fronts: the 20%–30% rise in home prices from pre-COVID levels and increasing mortgage rates. Consequently, we expect limited affordability to be a key driver in slowing home price appreciation in the coming months, settling around a pace reminiscent of the 1990s and 2000s.

Yet we do not believe overall price levels are problematic. The fastest run-up in prices occurred in comparatively affordable areas of the country (e.g., Texas and Arizona), as well as in suburbs and exurbs, largely driven by pandemic-related moves away from city centers. Many of these areas are still a long way from becoming as unaffordable as the major coastal cities. In addition, rents have recently risen and buying remains a comparatively cheap option. Therefore, while affordability merits monitoring, we believe the housing market should be able to absorb a moderate increase in mortgage rates. During the previous rising rate cycle, mortgage rates reached 5% in 2018, causing house-price appreciation to moderate in the least affordable regions, including the San Francisco Bay Area, which is what we expect as mortgage rates are reaching similar levels in the current cycle.

Single-family rental operators: a new source of support

Single-family rentals (SFRs) have long been a durable component of the national housing landscape and could further support the housing market in coming years. In the wake of the GFC’s market dislocations, institutional operators (>100 units) entered market areas that had been previously dominated by small-scale “mom-and-pop” managers (<10 units). Private equity firms led cash purchases of foreclosures, leasing the properties at high rental yields that compensated for the loss of efficiency in scattered-site property management. This new capital helped stabilize house prices in many of the worst-hit areas.

Since then, this distressed trade has evolved into sustainable institutional businesses in many areas, including Charlotte, Atlanta, Memphis, Las Vegas, Nashville, Orlando, Jacksonville, and Phoenix, and will likely continue growing in the coming years. Prominent among those developments is build-to-rent, which provides the ability to better target optimal neighborhoods and increase property-management efficiency through increased density. Still, the institutional SFRs tend to share the same narrow requisites: median prices, newer construction, good school districts, and temperate climate, limiting their impact on housing supply to relatively few areas.

Indeed, it remains to be seen how important institutional ownership will prove for housing nationally, as their share is still too small to have a large impact. To be sure, the areas with the highest concentrations of institutionally owned SFRs – those averaging at least 5% of sales in 2021 – accounted for just 4.1% of national transactions. However, these institutions could act as another shock absorber where they are most prevalent.

Investment implications: Housing-related structured finance remains attractive

In our view, U.S. housing prices should prove resilient, absent unexpected severe regional or national economic shocks. As such, we believe that securitized housing-related assets will remain a resilient source of attractive returns within the wider credit markets. We continue to favor the legacy non-agency mortgage sector, which lacks a dedicated investor base and has a very low loan-to-value ratio on seasoned loans.

We are also seeing increasing opportunities in new issuance, which reached a post-GFC high in 2021. The jumbo market and reperforming loans are no longer the main source of mortgage issuance, as updated pricing from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac has shifted some of the non-owner occupied production to the private markets. Agency credit risk transfers (CRT) are also poised to continue to grow as a sector, given that the Federal Housing Finance Agency’s (FHFA) recently revised capital rule provides the GSEs twice the capital relief for CRT issuance. Lastly, the non-qualified mortgage market has resumed production in earnest following its shutdown during the pandemic, and should provide another source of issuance. However, we remain extremely selective in sectors backed by recent originations, as these loans have not benefited from the run-up in house prices as much as more seasoned mortgages, and accordingly would not be as resilient in a downturn – careful security selection is critical.