There is no shortage of uncertainty as the new year begins, so in an attempt to provide some clarity, we briefly answer some of the key macro questions of 2021.

What does a Senate majority for the Democrats mean for the markets?

The Democratic sweep of Georgia gives the incoming administration some more legislative latitude, including around fiscal policies. However, with the narrowest of majorities in the Senate, the more progressive policies of the Democrats are likely off the table. Moderate, centrist Senators may have considerable sway in the new Congress. It seems likely the filibuster would remain in place for now. In terms of policy, we’re not expecting moon shots—think, rather, along more traditional lines: another coronavirus relief spending package, an infrastructure bill, more liberalization of trade and immigration, and some unwinding of the recent-era regulations on industry. For the broader economic/market environment and asset allocation, this means more upside to real gross domestic product (GDP) growth, inflation and interest rates and an increase in cyclical exposure across portfolios, in our view.

Do Deficits Matter?

No—at least not now. Rarely has deficit-spending been as warmly embraced by the financial markets as in the past 12 months given the massive need for government activism (aka spending) in the face of the growth-inhibiting pandemic and widening income inequality-cum-social instability. The bond vigilantes are hibernating—you would think a projected federal budget deficit of $3.3 trillion in fiscal year 2020 would result in “sticker shock” for investors, but that is currently not the case. Deficit spending will likely remain the norm over the medium term, supported by strong demand for U.S. Treasurys, low interest rates, the dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency, and the ability of the U.S. government to manufacture as many dollars as needed. In terms of asset allocation and portfolio positioning, we are very mindful of the U.S. deficit and its potential longterm effects (i.e., higher interest costs, crowding-out effects, etc.) But that said, in lieu of the pandemic-cum-U.S. recession, the markets are very comfortable (demanding) of deficit spending.

Is Inflation Dead?

No—and inflation is expected to perk up this year as pent-up consumer demand runs high long into truncated supplies. As the St. Louis Fed warned in December, Americans may have to “prepare themselves for a temporary burst of inflation.” But the key word here is “temporary.” A transitory rise in prices is expected this year, but a slack labor market, rising productivity, and demographic headwinds should keep a lid on a sustained and sizable move up in inflation. Think less “deflation” and more “reflation,” which is bullish for equities, notably cyclicals. We would not abandon the growth side of the markets, however, as we continue to emphasize the need for both growth and value characteristics in a portfolio for a potentially more diversified advancement in the next couple of years.

U.S.-China relations: Sweet or Sour in 2021?

Less sour but certainly not sweet. Investors shouldn’t expect a major U.S.-China reset given that America’s adversarial posture toward China is bipartisan in nature. Anti-China sentiment runs strong on both sides of the political aisle. Accordingly, the new administration is not expected to roll back the tariffs the Trump administration imposed on two-thirds of imports from China. And we don’t expect anything resembling détente over export controls, and competing tech standards. That said, however, the tone governing U.S.-China relations—while remaining stern—may become less confrontational, more orderly, and hopefully more constructive as the world’s two largest economies seek paths of mutual interest. In the last few years, U.S.-Sino relations became a magnet for volatility, supply chain disruptions and earnings pressure; these negative forces are likely to ameliorate somewhat in the coming years.

Can the incoming administration restore a semblance of global order?

Yes, but the world isn’t about to revert to the traditional days of U.S.-led globalization. The incoming administration is more multilaterally minded than the outgoing regime—watch for the U.S. to rejoin the Paris Agreement treaty on climate change, reaffirm its commitment to North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and add its weight to the continued viability of the World Trade Organization and other key institutions like the World Health Organization. All of the above is bullish for U.S. multinationals, the Industrial sector and heavy asset owners, in our opinion. However, after four years of uncertainty and pandemic-related global strains, the global economy is fragmenting along regional lines. Globalization isn’t dead, but it is becoming less U.S.-centric and driven by a more integrated Asia and autonomy-seeking Europe. Importantly, as it pertains to global affairs, the new administration will likely be more amendable to trade liberalization (i.e., joining more trade partnerships) and immigration reform—both variables are likely bullish for the long-term growth of U.S. corporate earnings.

What is one key lesson of the pandemic?

One key lesson: health=wealth. If we have learned anything from the coronavirus pandemic, it’s that health is a fundamental determinant to economic growth. The healthier the population, the stronger, more dynamic the nation’s human capital and the more competitive the economy. Less healthy nations, in contrast, are handicapped in terms of production, consumption and aggregate growth.

That said, it took a pandemic to expose the fragility of the global healthcare infrastructure. Global healthcare expenditures have climbed steadily over the past two decades, reaching nearly $8 trillion in 2017 (the last year of available data). However, spending on global healthcare as a percentage of world GDP has barely budged, flatlining at around 9% to 10% over the past two decades. So even before the coronavirus hit, the world’s healthcare infrastructure was straining at the seams. In the post-pandemic world, global healthcare expenditures are set to accelerate, a bullish prospect for world leaders in pharmaceuticals, diagnostic equipment, medical software/hardware, telemedicine and related medical goods and services.

Could the U.S. dollar continue to weaken this year?

Yes, but moderately over the next twelve months. In March 2020 as the pandemic swept the world, the U.S. dollar initially strengthened but has subsequently declined by roughly 12% on a trade-weighted basis, with the downside fueled in large part by uber-loose monetary policies of the Fed. The latter has compressed U.S. interest rates on both ends of the yield curve relative to global interest rates, undercutting the attractiveness of the buck. The soft dollar trend is set to likely continue, and is supportive of non-U.S. economies, notably the emerging markets, and reflation assets like cyclicals, commodities, and emerging market stocks and bonds. A weaker dollar is also a historical tailwind for the earnings of U.S. multinationals.

Should investors stick with market-leading technology equities?

Yes, we maintain our overweight to Information Technology and view the recent pullback in various tech leaders as an attractive entry point for long-term investors or those lacking tech exposure. As outlined in the January Viewpoint, we have increased our cyclical exposure to Industrials, Financials and Materials, yet remain long-term investors in Technology for a number of reasons, ranging from the pandemic induced boost to the digital global economy, rising capital expenditures (capex) spending in productivity enhancing technology, and the fact that over two billion people have yet to log on to the internet. Increased U.S. spending on infrastructure—think 5G, electrical vehicles and renewable energy—is also supportive for Technology for the long term.

What are the key risks to the economy/market outlook this year?

The risks run the gamut and include overly optimistic market sentiment in the U.S.— setting up for a market correction later this yea —to an unexpected geopolitical event, with U.S.-Sino tensions front and center. Other risks to watch carefully this year: a slower than-expected rollout of the vaccine, mounting inflationary pressures and the response of the Fed, and excessive government activism. Lastly, any potential changes regarding tax policy and/regulations under the new administration that are growth inhibiting would likely dent market sentiment and induce negative market volatility, in our opinion.

What are your favorite themes entering 2021?

Our top themes for this year pivot around the C.H.I.Ps—or cyber security, HealthTech, infrastructure, and the platform economy. Summarizing: Cyber security spending is set to accelerate as more of the global economy goes digital and the number of cases of cybercrime/-hacks soars. The premium on public health has fused two of the economy’s largest sectors: Healthcare and Technology. Constructing the infrastructure of the 21st century entails billions of dollars in capital investment in 5-G, renewable energies and electrical vehicles. And the future of the U.S. economy (and global economy) increasingly rests on the platform economy, with more and more platform companies disrupting and controlling an increasing share of aggregate output.

With 2020 Hindsight, Markets Look Toward 2021

Who could have imagined the events of 2020? A global pandemic, the sharpest market downturn on record, extraordinary stimulus measures from the Fed and a dizzying market comeback amid a contentious presidential election. While the economy remains off its pre-pandemic levels by a number of measures, the equity market charted a different story by year-end.

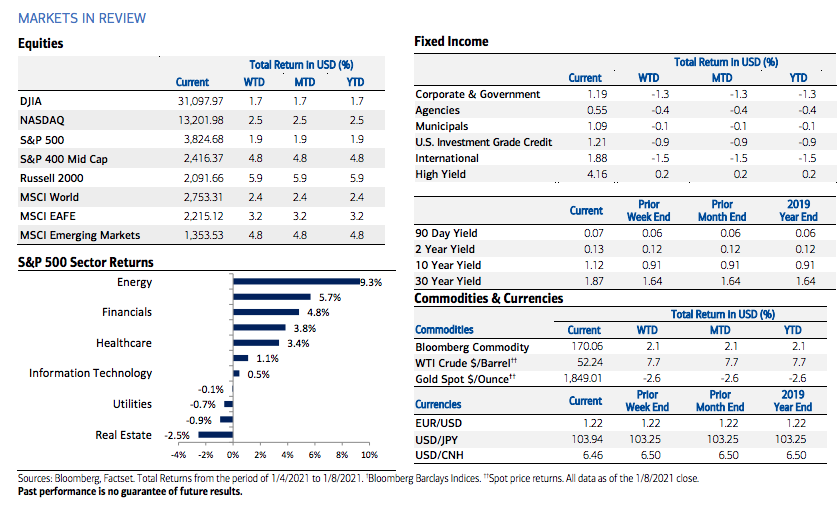

Capping the year, the S&P 500 ended 16.26% (18.4% Total Return (TF) higher for 2020 and has gained almost 50%1 over the past two years—its largest two-year gain since The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) added over 2,000 points, or 7.25% (9.7% TR) in 2020, while far behind the tech-heavy Nasdaq Composite gain of 43.6% (45.1% TR).

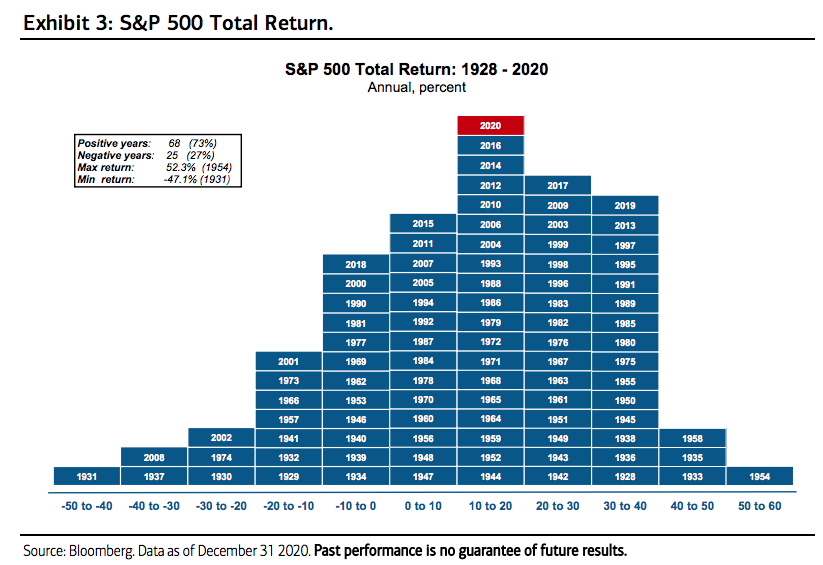

An incredible year indeed for U.S. equities after a drastic selloff in February and March, set against a backdrop of human and economic devastation. Historically speaking, returns on the S&P 500 have run the gamut (Exhibit 3). As for the best year (1954), the S&P 500 gained 52%, while the worst year (1931), the S&P 500 lost 47%.

Since inception, the S&P 500 has impressively ended in positive territory 73% of the time. Globally, the picture finished mixed with the MSCI Emerging Markets Index (+18.3%) in line with the S&P’s advance. Both gauges outpaced the MSCI Europe Index (+5.25%). The U.S. outperformed the rest of the world as measured by the MSCI All World ex-U.S. Index by at least 7%.

While there’s no shortage of remarks that can be made about last year, the averages suggest 2020 was an abnormal year with above-average returns. As we turn the calendar page, we do see positive trends building for economic and earnings growth into the new year supportive of an equity uptrend in 2021.