This article first appeared at The Wall Street Journal

ByChuin-Wei Yap and Jon EmontUpdated Feb. 23, 2020 12:22 pm ET

HONG KONG—The last time a coronavirus outbreak hit China in 2003, the global economy emerged relatively unscathed. Now, nearly two decades later, the growth-damping effects of a similar pathogen threaten to ripple around a world transformed by China’s boom.

Chinese consumption and production power growth from Asia to North America, Europe and beyond. Manufacturers world-wide are tethered to China by the tentacles of a supply chain that relies on the country’s factories for many intermediate and finished goods.

With fears of contagion keeping Chinese workers home, production is getting pinched. In the U.S., General Motors Co. unions have warned that a lack of China-made parts could slow assembly lines at sport-utility vehicle plants in Michigan and Texas; the company said it is working to mitigate the risk. Elsewhere, the story is the same—even in places that might seem remote.

Mostafiz Uddin, a bluejeans manufacturer in the southeastern Bangladeshi city of Chittagong, said he has been unable to fulfill an order for 100,000 women’s jeans because he can’t get the fabric he needs from China. “I am just waiting,” he said. “We have no option.”

A month after the epidemic forced factories into limbo past their usual Lunar New Year break—a handful are reopening—officials and economists are warning that an extended Chinese shutdown could cripple global manufacturing and cost the world up to $1 trillion in lost output.

“The current situation is more serious than we thought,” South Korean President Moon Jae-in said on Tuesday. “We need to take emergency steps in this time of emergency.”

Hyundai Motor Co.,after shutting some of its Chinese factories this month, suspended one of its main assembly lines in Ulsan, a big South Korean city, because it couldn’t get parts from China. Asiana Airlines Inc., South Korea’s second-largest airline, put its 10,500 employees on staggered shifts of 10 days’ unpaid leave from Wednesday.

Major electronics producers that depend on Chinese parts also have suspended output because of the outbreak. Others are weighing relocation. Japan’s exports to China are expected to drop 7% this quarter from the prior one, NLI Research Institute economist Taro Saito said. Videogame giant Nintendo Co. said this month that some shipments of its flagship Switch gaming console are delayed as it can’t get parts from Chinese factories.

Piling onto two years of China-U.S. trade tensions, the impact of the new coronavirus, which has killed more than 2,000 people in China, could be severe. Countries most reliant on China could see more than half a percentage point wiped off their gross domestic product this year, some economists say.

China now accounts for nearly a third of world GDP growth, up from around 3% in 2000. Between 2000 and 2017, the world’s economic exposure to China tripled, according to estimates by the McKinsey Global Institute.

That rising dependence weighs most heavily on Asia. In 2000, China accounted for just 1.2% of global trade, said the World Bank. Its share was one-third in 2018. In Asia, that measure went from 16% to 41% during the period.

The impact is felt everywhere. Apple Inc.said it won’t meet revenue projections for the first quarter as the epidemic shuts its China plants. In Europe, container-ship operators are preparing profit warnings as dozens of trips out of China are canceled.

A U.S. freeze on visitors from China is a blow to hotels and retailers that rely on their spending. Asian economies that have grown dependent on Chinese visitors and commerce are reeling. Singapore last week cut its annual GDP forecast to around 0.5%, down from 1.5%. Thailand estimates tourist arrivals could drop by 13% this year as Chinese are grounded.

In Vietnam, a small economy highly dependent on Chinese supply chains, exports in January fell 17.4% year-to-year to their second-lowest level since the U.S.-China trade war began, official data showed. Imports were down 13.7%, led by a 16% plunge in those from China.

From steel to furniture, Vietnam built much of its economy on importing semifinished material from China, then exporting the finished products to developed economies such as the U.S. Now, over 50% of manufacturers are experiencing difficulty sourcing supplies because of disruptions from the coronavirus, the American Chamber of Commerce in Vietnam said last week.

Australia, with an economy six times as large as Vietnam’s, is also feeling the effects. Two decades ago, China was a relatively peripheral trading partner, trailing the U.S., Japan and Korea as export destinations.

But as Beijing massively invested in industry, China’s enormous hunger sucked up ever larger shipments of iron ore and coal from the continent. Last year, China accounted for nearly 40% of Australia’s exports.

Australia’s BHP Billiton Ltd., the world’s largest miner, said it expects to revise its expectations for commodity-demand growth downward if the epidemic isn’t contained by the end of March.

The downturn also has spilled over to ancillary industries. Sydney-based WiseTech Global Ltd., which provides cloud-based software to track products, downgraded its 2020 earnings forecast Wednesday, saying China’s shutdown had forced a delay of new product features it had hoped would lift revenue.

“This is a once-in-a-generation event,” said Chief Executive Richard White.

—Timothy W. Martin, Stuart Condie and Megumi Fujikawa contributed to this article.

Drugmaker Moderna Delivers First Experimental Coronavirus Vaccine for Human Testing

Clinical trial is expected to start in April, as epidemic originating in China spurs quick response

ByPeter LoftusFeb. 24, 2020 4:18 pm ET

Drugmaker Moderna Inc. has shipped the first batch of its rapidly developed coronavirus vaccine to U.S. government researchers, who will launch the first human tests of whether the experimental shot could help suppress the epidemic originating in China.

Moderna on Monday sent vaccine vials from its Norwood, Mass., manufacturing plant to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Bethesda, Md., the company said. The institute expects by the end of April to start a clinical trial of about 20 to 25 healthy volunteers, testing whether two doses of the shot are safe and induce an immune response likely to protect against infection, NIAID Director Anthony Fauci said in an interview. Initial results could become available in July or August.

Moderna’s turnaround time in producing the first batch of the vaccine—co-designed with NIAID, after learning the new virus’s genetic sequence in January—is a stunningly fast response to an emerging outbreak.

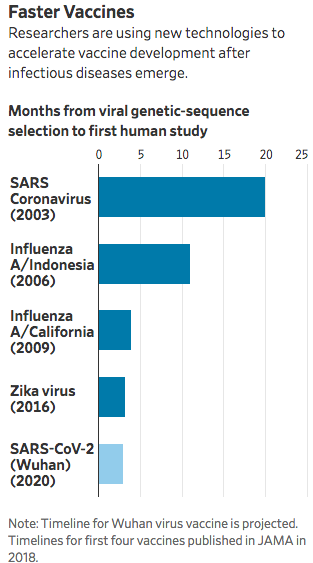

If a trial starts as planned in April, it would be about three months from vaccine design to human testing. In comparison, after an outbreak of an older coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome, in China in 2002, it took about 20 months for NIAID to get a vaccine into the first stage of human testing, according to Dr. Fauci.

“Going into a Phase One trial within three months of getting the sequence is unquestionably the world indoor record. Nothing has ever gone that fast,” Dr. Fauci said.

Public-health authorities say advances in vaccine technology, aided by government and private investments, are shortening development timelines when outbreaks occur. In the past, researchers scrambled to develop vaccines in response to outbreaks such as SARS, Ebola and Zika with mixed results. Older types of vaccines are developed from viral proteins that must be grown in eggs or cell cultures, and together with animal testing it can take years before a vaccine can be used in humans.

Newer approaches rely on what are known as platform technologies—building blocks that can be tweaked quickly with the genetic information from a newly emerged pathogen.

The fast production of a vaccine and plans to test it soon don’t guarantee its success. “You’re never sure until you’re at the end what you have,” said Bruce Gellin, president of global immunization at the Sabin Vaccine Institute. Saying there are other coronavirus vaccines in the works, he added: “The sequence of testing is designed to sort out what works from what doesn’t. That’s why it’s important to try as many things as possible that seem feasible, because not all horses will finish the race.”

It is uncertain whether Moderna’s vaccine will work because its gene-based technology hasn’t yet yielded an approved human vaccine. And even if the first study is positive, the coronavirus vaccine might not become widely available until next year because further studies and regulatory clearances will be needed, Dr. Fauci said.

But health authorities say it is worth placing bets on these new technologies in the face of fast-moving outbreaks. Since early January, when only a few dozen cases were confirmed in central China, the virus has spread to more than 78,000 people, including more than 2,400 who have died. The vast majority of the cases are in China, according to the World Health Organization.

Dr. Fauci said it is possible the spread of coronavirus could lessen during warmer months, but then return next winter and become a seasonal virus like the flu, making a vaccine useful even if it isn’t ready for widespread distribution until next year.

“The only way you can completely suppress an emerging infectious disease is with a vaccine,” Dr. Fauci said in his office in Bethesda. “If you want to really get it quickly, you’re using technologies that are not as time-honored as the standard, what I call antiquated, way of doing it.”

Moderna, which has more than 800 employees, was founded in 2010 to develop drugs and vaccines based on what is known as messenger RNA, the genetic molecules that carry instructions from DNA to the body’s cells to make certain proteins. The company is targeting cancer, heart disease and infectious diseases. It hasn’t brought any drugs or vaccines to market.

Moderna Chief Executive Stephane Bancel said he got in touch with NIAID after hearing about the new China virus while vacationing with his family in France in early January, to discuss collaborating on a vaccine.

Chinese scientists found the genetic sequence of the new virus and published it online around Jan. 10. Researchers at NIAID and Moderna analyzed the sequence and homed in on a section they believed was most likely to induce the desired immune response if incorporated into a vaccine. NIAID agreed to run a clinical trial if Moderna could supply a vaccine.

Moderna didn’t need actual samples of the virus or its proteins. The company’s vaccines instead contain nucleic acids with genetic codes that instruct the body’s own cells to make certain proteins from the virus that don’t infect a person, but trigger an immune response.

Moderna in 2018 opened a manufacturing site in the shell of a former Polaroid plant in Norwood, near the company’s Cambridge, Mass., headquarters. In the plant, employees wearing white lab gowns, hair nets and safety goggles work amid lab hoods, robotic machinery and steel tanks to produce drugs and vaccines for clinical trials. Meeting rooms are named after famous scientists such as Curie and Pasteur.

To make the coronavirus vaccine, Moderna repurposed some of the robotic equipment that was making cancer vaccines tailored to the genetic mutations of patients’ tumors.

As many as 100 manufacturing and quality-control employees were involved in the effort, many working nights and weekends. As manufacturing ramped up, the company’s leaders had frequent meetings, calls and WhatsApp messaging chains to monitor progress, and stayed in close contact with NIAID.

After Moderna’s effort became public in January, friends and family members became interested.

Juan Andres, Moderna’s head of technical operations, said, “I wasn’t used to my kid thinking I did anything cool,” but his 15-year-old son began asking questions about the project at dinner.

Moderna finished manufacturing about 500 vials on Feb. 7, a Friday. Normally, the company would have waited until Monday to start quality-control tests, but about 10 to 15 workers spent the weekend testing samples for potency and other features. The batch cleared most tests that weekend, but it took about two weeks to complete sterility testing. Moderna stored the supply in freezers set to minus-70 degrees Celsius.

One risk of moving so fast is that Moderna and NIAID won’t know for sure they picked the best fragment of the virus’s genetic sequence to target until the human study is completed.

“It is possible it’s going to work, but we have to wait and see,” said Mr. Bancel, Moderna’s CEO.

The first trial will be conducted at NIAID’s clinical-trials unit in Bethesda. If the first one is successful, a second trial of hundreds or thousands of participants could begin, which could take six to eight months, Dr. Fauci said. This trial could be conducted partly in the U.S. but also in China or a region where the virus is spreading, so the testing could gauge whether the vaccine reduces infection rates.

If the second trial is positive, the vaccine could be ready for widespread use, he said. How widely the virus has spread by then will determine whether it is given to targeted groups such as health-care workers, or more broadly to the general population, Dr. Fauci said.